I watched Adolescence in one sitting. Ten minutes later, I was messaging all my parent and teacher friends: “Have you seen this yet?”

Then, after talking it through with my husband, mostly about the kinds of conversations we'll need to have with our now 16-month-old son, I washed my face (after ugly crying at the closing scenes), went to bed, and lay awake staring at the ceiling.

A quick Google search the next morning – “Is Adolescence a true story?” – confirmed it was fictional. But for many young people today, the issues it explores - misogyny, incel culture, toxic masculinity, knife crime, and online harms - are very real.

Teachers are already seeing the effects. In a recent survey, 76% of secondary and 60% of primary teachers said they were seriously concerned about the influence of online misogyny. One pupil reportedly said, “It’s okay to hurt women because Andrew Tate does it”.

In the year ending March 2024, over 3,200 knife offences were committed by children. And between 2018 and 2022, the number of women killed, injured, or threatened with a knife more than doubled.

Adolescence may be fiction. But what it reflects is happening now.

‘I read an article in the paper [...] about a young girl who had been stabbed to death by a young boy and then a couple months later I was watching the news and there was another story about a young boy who stabbed a girl to death and if I’m really honest with you, it hurt my heart and I just thought as a parent as well. It just kind of made me think…What’s going on with society? What’s happening today where this is becoming a regular occurrence?’

Stephen Graham (co-writer & cast member), in an interview with This Morning

With Sir Keir Starmer recently backing calls to show the series in schools and the Tories pressuring the government to enforce phone bans, it's becoming another moment in which teachers are expected to implement top-down suggestions without the support to match. Everyone has an opinion, but few see the reality in classrooms.

For teachers already juggling relentless demands, it’s hard to know which advice to listen to, and frustrating when it feels like the world forgets that these issues are already showing up in schools every day. This blog explores the themes raised in Adolescence and offers practical ways to open up safe, meaningful conversations, without having to throw away your curriculum plans to find the time to show a full Netflix series in class.

The generational divide is real and the show doesn’t shy away from underlining the problems we have as a society in understanding young people’s behaviour - how they communicate, navigate the online world, and the ways they can be radicalised. There are several moments that remind us that, if we want to step in before things spiral, we need to actively listen and talk to young people - not just about what they’re doing, but how they’re feeling and what they’re seeing.

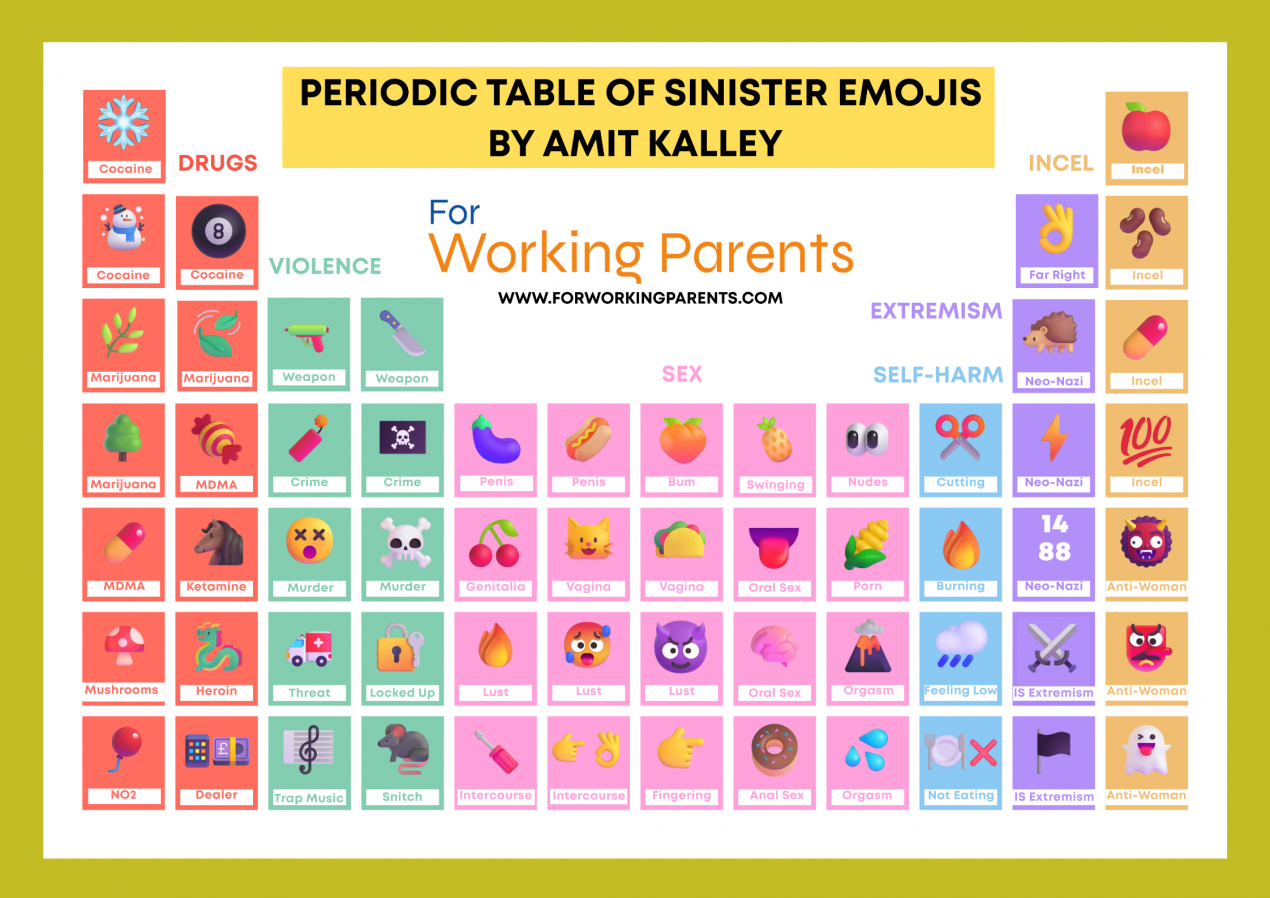

There’s a poignant moment in the second episode where the DI’s son takes his dad aside and tells him he’s looking in the wrong place. The clues are in the emojis, not just in words and actions. I thought I was fluent enough in emojis to understand a comment under an Instagram post. I was completely wrong. I had no idea that a red pill, dynamite, 100, or kidney beans had anything to do with incel culture or the manosphere - or that the colour of a heart could say so much.

Hats off to For Working Parents for creating this reference tool on the potential hidden meanings to some emojis - now recommended by UK police for use in schools. As The Telegraph rightly points out, awareness is everything, and resources like this can help teachers be more in the know about language students might be exposed to.

Download NowWe often focus on what we think young people need to learn, and overlook what they can teach us. But in the classroom, that curiosity - the willingness to ask, to explore their world without judgement - is everything. It’s how we open the door to honest conversations, challenge harmful ideas and help students feel seen, heard, and safe.

How often have you heard older generations say “god I’m getting old. These youngsters nowadays doing xyz. I don’t understand”. It’s fair enough, we do get old and new tendencies move in fast but we need to move with it to support young people.

At VotesforSchools we asked the question, “Are older generations equipped to teach young people about the online world?” and while 86% of our 5-11 aged voters voted “yes”, our 11-16 and 16+ voters voted “no”. One of the main reasons Secondary, College & 16+ students gave was that adults have had a very different experience of being online compared to today and don’t necessarily have the specific skills to help. Others argued that it is difficult for adults to keep up with the pace of the online world.

As teachers, we want to encourage respect, empathy, and allyship but we also know that expecting students to challenge their peers isn’t always realistic, especially if they don’t feel safe or supported. That’s why the groundwork matters. It’s not about one-off assemblies or PSHE lessons but about creating a culture where sexist behaviour is noticed, challenged, and not brushed off as “just a joke”. Sometimes, that starts with small, everyday conversations - noticing the language used, questioning the source of a comment, or simply making space for students to reflect without fear of judgement.

It’s not a quick fix but it is something we can do - one conversation, one safe classroom, one raised eyebrow at a time.

"It’s not our fault. We can’t blame ourselves."

"But we made him, didn’t we?"

That line really stuck with me. A friend of mine had never heard of incel culture before watching Adolescence but afterwards she started looking into it - reading about the language, the communities, the red flags. The show did what good storytelling can: it started conversations, brought difficult topics like misogyny and radicalisation into the mainstream, and made people pay attention.

However the reality is more complex. Not every student who uses incel terms or misogynistic language sees themselves as part of that world. Often, the language just trickles down from online spaces into everyday conversations and it can be easy to miss. That’s what makes it so hard to spot - and so important to talk about.

Schools are part of the Prevent Duty and most staff get training on how to spot signs of radicalisation, but trends change fast. What shows up in a classroom or corridor today might be completely different a month from now. And it’s not just on schools - parents are navigating this too, often without the tools to know what to look for. That quiet moment in the series where the parents wonder if they could have done more, thinking back to all those hours spent alone online? That hit hard because we’ve all had that thought, either as parents or teachers.

Banning phones might feel like a quick fix - and sure, it crossed my mind too - but even with restrictions, the online world doesn’t stop at the school gates. While we can’t control every corner of the internet, we can create space in school to help students make sense of what they’re seeing, promote online safety, and open up the conversation with parents so they feel part of it too.

‘This is a show about a kid who does the wrong thing and causes great harm. To understand him, we have to understand the pressures upon him [...] Jamie has been polluted by ideas that he's heard online, that make sense to him, that have a logic that's attractive to him, that answer the questions as to his loneliness and isolation and lead him to make some very bad choices.’

Jack Thorne, co-creator of Adolescence

The series lays bare the real-life consequences of toxic masculinity and how the online content that some boys may encounter, from violent pornography to influencers sharing outdated, harmful views, can distort their understanding of relationships, their perception of women, and what they believe “normal” male behaviour looks like. As the creators put it, they wanted to ‘look in the eye of male rage’.

Comments made by Jamie to the child psychologist sent shivers down my spine but what’s even more unsettling is how widespread some of these attitudes are. In a recent London workshop, boys as young as 13 admitted to watching porn, sharing explicit images of classmates, and rating girls based on their looks. Female students described being told what to wear, hearing violent threats, and being subjected to degrading comments inspired by Andrew Tate. One girl explained how boys at her school use Tate’s hand gestures as a kind of in-joke — a way to show solidarity with him, and to demean girls.

Of the 19 boys spoken to across different schools, some recognised their behaviour was wrong but said they’d do it again anyway. One student admitted he wanted to call it out but didn’t feel safe. While some boys did show respectful attitudes, the majority had normalised behaviour that girls later described as “extremely oppressive.”

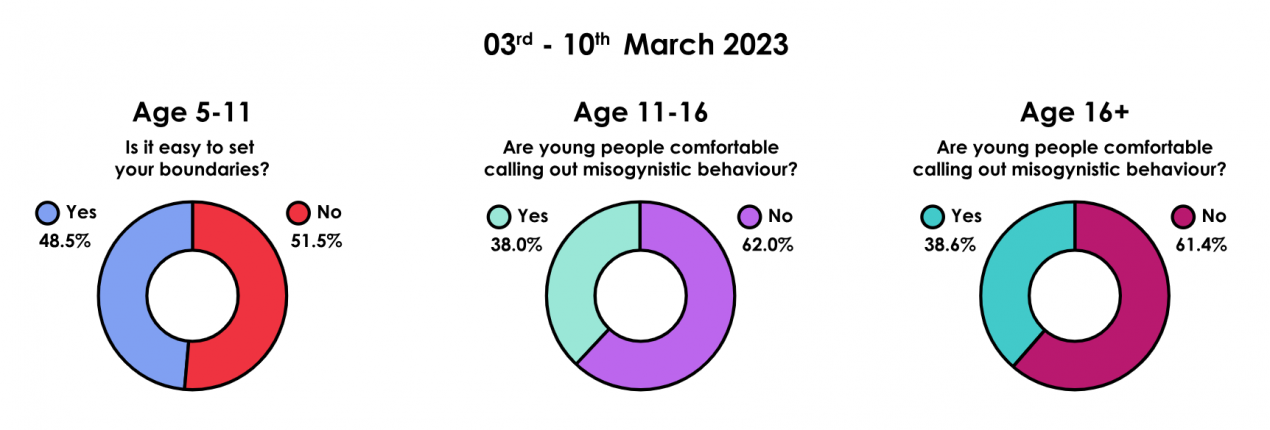

This highlights just how embedded these ideas are - and how difficult it is for young people to challenge them. In 2023, VotesforSchools asked young people if they felt comfortable calling out misogynistic behaviour. 18,657 responded, with 62% voting 'no'. Many feared losing friends. Others feared violence.

I think one of the reasons Adolescence is so powerful is that it feels so familiar. While watching, I found myself thinking, “That looks like my school,” or “That neighbourhood feels like mine.” When the detectives try to understand Jamie’s actions, they start by asking about his family - and the answers are surprisingly ordinary. Two working parents trying their best to juggle home life and work. Nothing out of the ordinary.

That’s what makes it unsettling: it could happen to anyone, anywhere. No one is immune to the reach of the online world or the influence of harmful content. That’s part of what Adolescence does so effectively - it challenges our assumptions about 'the kind of family' or 'the kind of child' who ends up in this situation. There’s no clear villain, no easy answer. As Graham puts it, “It takes a village to raise a child, but also a village to destroy a child.”

So where does that leave us as teachers, parents, or people in the community who care about young people’s wellbeing? Maybe it’s not about placing blame but recognising the part we each play. For schools, it’s about creating space for students to ask questions, challenge stereotypes, and talk openly about what they’re seeing and hearing online.

If you’re not sure where to start, our blog on tackling misogyny in the classroom offers practical strategies and reflection points for approaching these conversations with confidence. Because while we might not be able to control everything our students are exposed to, we can equip them with the tools to think critically, speak up, and seek help when they need it.

In a recent speech, Sir Gareth Southgate said there was a need for better role models rather than turning to ‘manipulative and toxic influencers, whose sole drive is for their own gain’ and who ‘don’t have their best interests at heart.’

Meanwhile the Prime Minister said the series was ‘a wake-up call’. He has called for the series to be screened in Parliament and to be integrated into the school curriculum to combat online misogyny and to promote healthy attitudes in young people. Also, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson has launched an investigation into smartphones being used in schools following calls from MPs to take stronger action against the harmful effects of social media.

We know how challenging it can be to navigate these complex issues. When Graham talks about it taking a village to raise or destroy a child, it hits home because teachers are often right at the heart of that village. You’re juggling so many roles: educator, mentor, protector and sometimes it feels overwhelming.

But you’re not in it alone. Here at VotesforSchools, we help teachers navigate sensitive discussions involving misogyny, incel culture, knife crime, and the online world. The conversations sparked by our resources help our young people to be heard and bring about positive change. We recognise that it’s not about placing blame but about working together as a community - schools, families, and wider society - to build a safer and more supportive environment for young people.

We know it’s tough but every conversation you have, every lesson you deliver, and every bit of empathy you show makes a difference. We’re here to help you continue that vital work.

As the credits rolled, I wondered what the fate of the Miller’s would be. I also wondered about Katie’s family, whose names we barely hear mentioned in the series.

I want to ask, ‘What’s next?’- not ‘Who’s next?’

This article was written by our intern, Emma. She has a degree in languages and has lived abroad teaching English as a Second Language. Having studied Film at university, she is passionate about the importance of portraying social issues in film and TV to bring awareness, create conversations and drive change.