Real life doesn’t follow a scheme of work

Why PSHE & Personal Development needs to prepare pupils for the world they’re living in — not last year’s plan

Let’s be honest: the world young people are growing up in updates faster than our curriculum maps.

It feels like just a few months ago ChatGPT burst onto the scene. Now AI is everywhere — and not always in ways we’d choose. And it’s not just AI. News travels at warp speed too. A headline breaks and, before you’ve even skimmed it, pupils have already formed opinions, swapped screenshots, and started debating it in the corridor.

And when you’ve got a packed timetable and a never-ending list of “must-dos”, it’s easy to default to the safe option:

We’ve got a lesson to teach. There’s no time to go off-topic.

But there’s always that niggling sense that we’re missing something. That we’re walking past real opportunities to do what PSHE and Personal Development are meant to do: help pupils make sense of the world — and learn how to live well in it.

Because here’s the thing: Personal Development is happening all the time.

If we don’t help pupils navigate what they’re seeing, hearing, and experiencing, they’ll still navigate it… just without the language, structure, or safety net we can provide.

Planning matters — but so does relevance

I’m not here to bash planning. Schemes of work exist for good reasons. They bring structure, consistency and (let’s be real) a bit of peace of mind.

But they also come with a problem we don’t talk about enough:

Real life doesn’t arrive neatly in “Autumn 2” or “Summer 1”.

So when a major report lands about platforms pushing harmful content to teens, where does it go?

- Into a quick assembly most pupils half-hear?

- Saved for next term when “social media” comes round again?

- Or do we make space for it now, while it still matters?

If schools want outstanding PSHE and Personal Development, we already know the answer. The hard part is that the “right answer” is usually the one that adds pressure.

And this isn’t just a “PSHE problem” — it’s a PD one

Ofsted’s language around Personal Development is all about preparing pupils for life in modern Britain: confidence, resilience, understanding risk (online and offline), respectful relationships, and being informed and responsible citizens (Ofsted Education Inspection Framework (EIF)).

But Ofsted also isn’t asking leaders to produce a magic spreadsheet that proves “impact” on every individual child. The inspection handbook is clear that inspectors don’t try to measure the impact of a school’s work on the lives of individual pupils.

So what are we really trying to do?

We’re trying to build readiness — not just coverage.

Coverage isn’t readiness

A scheme can tell us we’ve “done” a topic.

But readiness is different. Readiness sounds like:

- “I can spot when something isn’t OK.”

- “I know how to say no.”

- “I can ask for help without feeling stupid.”

- “I can disagree without it turning nasty.”

- “I can think critically about what I’m seeing.”

And that gap — between teaching something once and pupils being able to use it — is where a lot of schools are feeling the strain.

You can see it in the bigger picture too:

- In England, 20.3% of 8–16 year olds had a probable mental disorder in 2023. (NHS England)

- Employers are saying young people often lack key social skills: 64% of employers report this gap in the workplace. (CIPD)

This isn’t about blaming schools. It’s about admitting the job has changed — and the model needs to change with it.

“Be responsive” is good advice… until you look at your diary

Most schools want PSHE and PD to be responsive. Most teachers want to make space for what pupils are bringing in.

But being responsive is hard when:

- staff confidence varies (especially with sensitive topics)

- time is tight

- cover happens

- the same topic lands differently depending on the class in front of you

- and the last thing anyone needs is another thing to plan

So the real question becomes:

How do you make responsiveness reliable — without making workload worse?

What responsive PSHE/PD looks like when it’s done well

The best examples I see in schools aren’t chaotic. They’re not “whatever’s in the news today, let’s panic-teach it.” They’re structured. Predictable. Safe.

Responsive PSHE/PD usually has four ingredients:

1) A weekly rhythm

A set slot — tutor time, PSHE, PD, assembly follow-up — where pupils know discussion happens. Not “when we get around to it”. A rhythm.

2) A safe structure for discussion

Staff shouldn’t have to invent the approach in the moment. High-quality sessions give you a clear question, boundaries and ground rules, prompts that move from surface opinions to reasoned thinking, and a way to close safely (especially if something heavy comes up).

3) Curriculum mapping without the admin

This is important. Schools still need to know they’re meeting expectations. But leaders and staff don’t have time to cross-reference the news with a PSHE scheme and then rewrite three slides to make it safe.

4) Low prep, high confidence

If “responsiveness” only works when a specialist teacher delivers it, it won’t scale. A good model works even when it’s a form tutor delivering it, a cover supervisor picking it up, or an ECT who’s brilliant but understandably nervous about tricky conversations.

A real example: AI advice (and why it matters)

Here’s what I mean by “real life moves fast”.

Young people are increasingly using AI tools for advice — sometimes harmlessly, sometimes for things that really need a human.

That’s not a future problem. That’s a right now problem.

A good PSHE/PD session here isn’t “AI is bad”. It’s:

- why AI can feel easy to talk to

- what it can and can’t do

- how to spot when something needs real support

- what good help-seeking actually looks like

- how to talk to a trusted adult (and what to say)

And the important bit: one real issue like this naturally touches multiple strands of PSHE and PD at once — critical thinking, influence, online safety, resilience, communication, help-seeking, relationships with adults, and more.

That’s why responsiveness isn’t “extra”. It is the curriculum, when you’re preparing pupils for life.

This is why schemes of work can’t do the job alone

Here’s the uncomfortable truth:

A scheme of work written in July can’t fully prepare young people for what lands in September.

Not because teachers aren’t brilliant. Because the job has changed. Pupils’ pressures and influences shift quickly — driven by online culture, the news cycle, and what’s happening locally.

A scheme can give you coverage.

But it won’t guarantee readiness.

How VotesforSchools helps schools build real-life readiness (without extra workload)

VotesforSchools was built around a simple idea:

Start with what’s happening now, then map it back to curriculum needs — not the other way around.

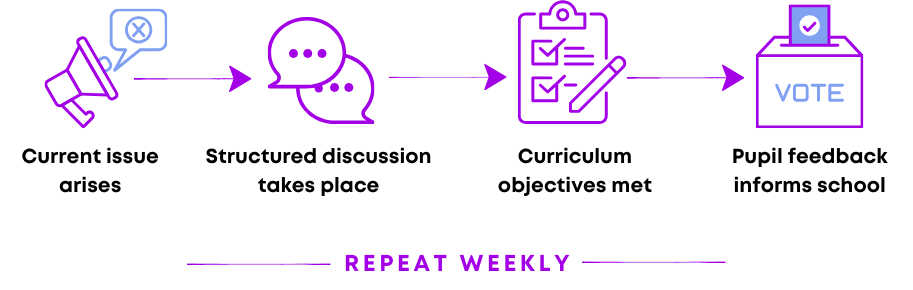

That’s why our lessons are created weekly, inspired directly by what’s happening in the world around young people, and mapped to PSHE, SMSC and British Values.

It’s also why the model is designed to be genuinely plug-and-play:

- everything needed is in the slides

- discussion is structured and age-appropriate

- delivery doesn’t depend on one specialist teacher

- the weekly routine builds pupil voice and confidence over time

A question worth asking

If you’re responsible for PSHE or Personal Development, here’s the question that matters:

Does your curriculum reflect this week’s world — or last year’s plan?

Because real life doesn’t follow a scheme of work. And if our job is to prepare pupils for modern Britain, our model has to acknowledge that.

See it in action for two weeks

If any of this has made you think, “Yes — but how would this actually work in our school?”, you’re not alone.

That’s exactly why we offer a free 2-week trial. It’s enough time to try the weekly lesson with your pupils, see the quality of discussion it creates, and get a feel for how easy it is to run — even when different staff are delivering.

Use the form below to start your free 2-week trial.